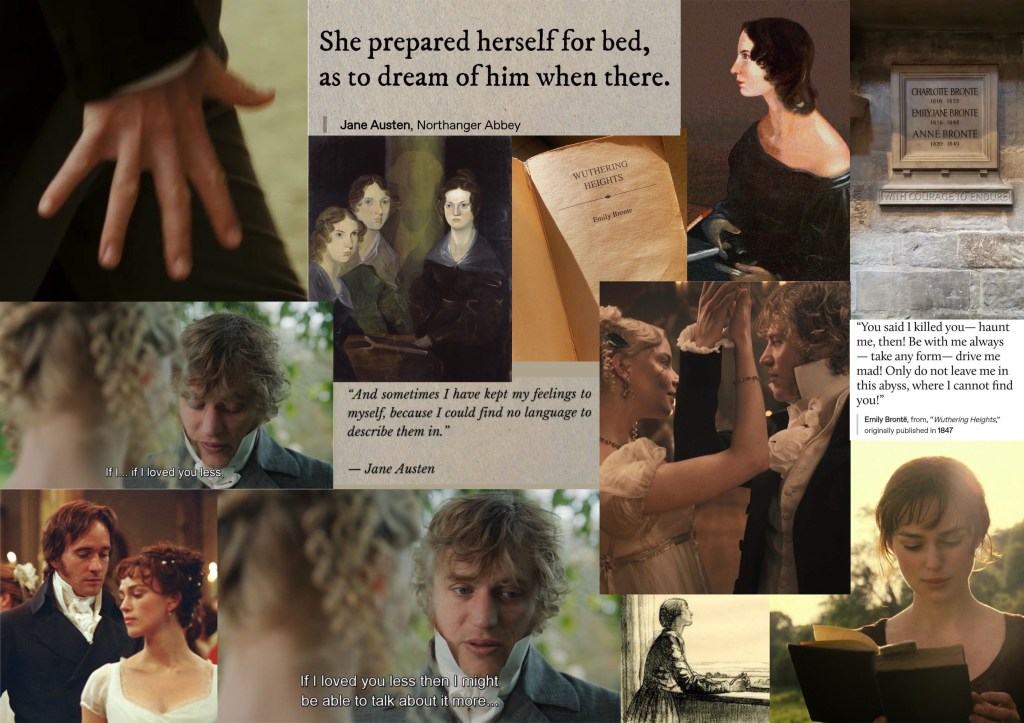

There is a peculiar irony that lingers in the pages of history: some of the greatest love stories ever written were crafted by women who never lived them. Jane Austen, who gave us the sharp-witted and swoon-worthy Mr. Darcy, never married. The Brontë sisters, whose novels are infused with lust and longing, lived quiet, uneventful lives, largely untouched by romance. Emily Dickinson, whose poetry reads like the breath of a love-stricken heart, spent much of her life in solitude, sending letters to an unnamed beloved who may never have truly existed.

And yet, these women captured love better than those who lived and lost it. Their words are corroded into our collective consciousness, their stories devoured by generations who turn to fiction in search of the love they cannot find in reality. Why is it that the women who understood love so deeply, who could write it into existence so convincingly, never found it for themselves?

To be a woman writer in the 18th and 19th centuries was to make a choice. The quiet comfort of marriage or the wild freedom of the mind. Few could have both. Marriage, for most women of that time, was a legal and financial transaction, one that rarely allowed room for creative ambition.

Jane Austen, whose novels overflow with canniness and romance, knew this reality all too well. She had her chances, there was Tom Lefroy, a youthful flirtation that was cut short by his family, and Harris Bigg-Wither, whom she briefly accepted before recoiling at the thought of a life bound in uninspired matrimony. In the end, Jane chose her pen over a ring, writing to her niece that “anything is to be preferred or endured rather than marrying without affection.”

The Brontës, too, lived in a world where marriage was often a compromise rather than a grand love affair. They were raised in near isolation on the Yorkshire moors, their imaginations fed by the rolling hills and the books they devoured. Emily Brontë, the most reclusive of the three, never married, never seemed to have a lover, and yet she wrote Wuthering Heights—a novel so feverish, so consumed by passion, that it seems impossible that it came from the mind of a woman who had never known love herself. Perhaps, for Emily, love existed more beautifully in her imagination than in reality.

It is natural to assume that a writer must experience these moments to write it well, but history proves otherwise. In fact, distance may have given these women an even greater ability to understand love. Free from the distractions of real-world relationships which are often messy, mundane, and often disappointing. They were able to construct love in its purest, most idealized form.

This may be why their love stories endure. Their understanding of romance was not clouded by the small, inevitable disenchantments of everyday life. They wrote of soulmates, of passion that defied reason, of love that burned so intensely it could only end in tragedy or eternity.

Emily Dickinson, for example, wrote poetry that oozed with longing. Her words were intimate, secretive, as though written in the dead of night for a lover she could never touch. “Wild nights—wild nights! / Were I with thee,” she wrote, though history gives us little proof that she was ever truly with anyone at all. Perhaps she didn’t need to be. The craving itself was enough.

Another aspect, a tale the modern woman now knows too well, is that maybe the reason why so many of these women never found love, is that they were simply too extraordinary for the time in which they lived. The men around them could not match their minds, could not keep up with their wit, could not understand the depths of their ambition.

Imagine being a woman in Austen’s time, capable of crafting dialogue so sharp it could draw blood, so perceptive it could dismantle an entire social structure in a single sentence. What man could keep up? Imagine being Emily Brontë, so enraptured by the profundity of her imagination that no earthly love could compare. Who could be her Heathcliff?

It is tempting to mourn for these women, to wish they had known the great, sweeping loves they so beautifully captured on the page. But perhaps, in some way, they did. Perhaps their love was not meant for one man, for one fleeting romance, but for something far greater. Their love was for the world, for the women who would read their words centuries later and find themselves within them.

Love, after all, is not just something to be lived—it is something to be imagined, to be felt, to be created. And in that, these women were never without it.

Would love have made their work greater, or would it have dulled the longing that made it so extraordinary?