In the past, artists struggled against kings, religious dogma, fascist regimes, and economic collapse. Today, they’re up against something far more slippery: the algorithm. It does not burn books or break brushes. It simply buries your work in silence.

We are living through a seismic shift in how art is seen, shared, and valued. And at the heart of it lies a question that no longer feels rhetorical: What happens to culture when creativity is filtered through code?

Once, the success of art was determined by its emotional impact—how it moved people, disturbed them, made them think. Now, success is defined by metrics: views, likes, comments, shares, saves. Social media platforms have become the default art galleries of our time, but they are not curated by humans with taste or emotional intelligence. They are ruled by machine-learning models trained to prioritize engagement, virality, and ad revenue. Which means, more often than not, the content that survives isn’t what’s meaningful—it’s what’s marketable.

This has birthed a new kind of creative anxiety: artists are constantly told they must “play the game” in order to be seen. That game includes packaging their work into ten second videos, trendy music, and caption hooks like “day six of revealing my art until it reaches its target audience…” or “go to part two to see the finished piece…” Not because that’s what their art demands, but because that’s what the algorithm prefers.

Perhaps more alarming than invisibility is visibility. Because if your art does go viral, it enters a mass digital critique in the comment section. There was a time when people stood in front of a painting or read a poem and reflected. Now they react. Instantly. Publicly. Often cruelly. Comment sections are no longer forums for discussion—they’re bloodbaths of projection, snark, and rage. No matter what you post—something vulnerable, political, abstract, or simply personal—it is inevitably met with a deluge of mockery, moral policing, or the casual brutality of “this sucks.”

This is particularly dangerous for emerging or sensitive artists, especially those from marginalized communities. The digital mob doesn’t care about context or creative intent. It thrives on controversy, misunderstanding, and dehumanization. The rise of “hate as engagement” means that outrage is incentivized. There’s no time for people to sit with work, to let it breathe. Instead, they scroll, judge, and move on, often leaving behind a trail of venomous comments that stick to the creator like static electricity.

The result is a new form of censorship—not the top-down, government-mandated kind, but something quieter and more insidious. Artists begin to self-censor. They avoid risk. They strip their work of complexity or nuance, fearing backlash. Or worse, they create for backlash, because in a system where rage boosts reach, controversy becomes strategy. Art becomes bait.

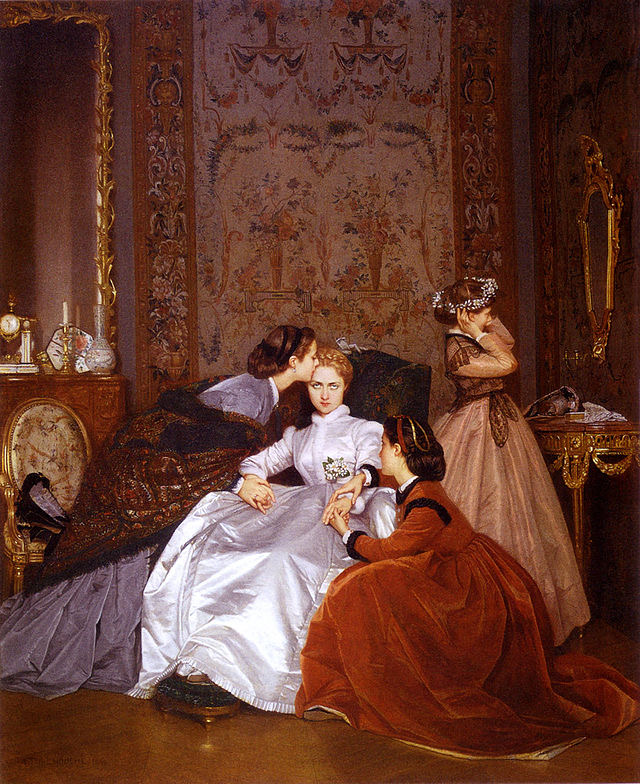

And yet, what gets lost in this system isn’t just the artist’s intention—it’s our own ability to feel. There is a particular stillness that settles over you when you walk through a gallery—like entering a sacred space where time slows and silence speaks. You don’t just look at a painting; you feel it. The scale, the texture, the brushstrokes—each one pulsing with the artist’s intention, their breath, their labor. You linger longer than you planned, drawn into color, shadow, and suggestion. You tilt your head, lean in, move around the frame. There’s intimacy, presence. You carry it with you.

But when art is reduced to a glowing rectangle on an iPhone screen, all of that disappears. You scroll past it in a second, barely registering the emotion, and if you do feel something—if a piece reaches you—it’s often crushed beneath comments full of mockery, cynicism, or armchair criticism. Someone will tell you why you’re wrong to love it. And then, just like that, you swipe away, and the feeling vanishes. What could have moved you for years is replaced with the next clip of someone dancing or selling skincare. You forget the art as quickly as you saw it. But the memory of seeing your favorite painting in a museum? That stays. You remember the room, the quiet, the goosebumps. Because no algorithm can replicate the ache of standing before something real.

We are not meant to consume art like this—in flashes, in fragments, on a screen coated in fingerprints. Art is not designed to be background noise while we wait in line or mindlessly scroll in bed. It’s meant to disturb, challenge, move, comfort, and wake us up. But how can it, when we aren’t allowed to sit with it long enough to even know what we feel? The problem is not that people don’t care about art anymore—it’s that the platforms we use to find it are hostile to slowness, depth, and human connection. They strip away the conditions necessary for transcendence.

And yet, people still crave art. That’s the paradox. In a world oversaturated with noise, people are starving for something real. But the platforms mediating our access to creativity are fundamentally hostile to the things that make art meaningful: slowness, solitude, struggle, subtlety. The algorithm doesn’t know what to do with a poem that makes you cry for reasons you can’t explain. It cannot quantify the stillness of looking at a painting and feeling your own memories resurface. It cannot measure resonance. It can only track reactions.

This is the new propaganda: not a loud campaign against art, but a quiet, consistent erasure of its value. It convinces us that if something doesn’t perform, it isn’t worth anything. That beauty must be functional. That artists are only valuable if they are influencers. That the self is a brand, not a vessel.