There is something about female rage… Something beautiful. Something terrifying. And throughout art history, it has been documented, commodified, feared, and worshipped in equal measure.

But then, sometimes, female rage doesn’t come with soft-focus lighting and a poetic backstory. Sometimes, it claws its way out in blood-red brushstrokes, in disjointed limbs and grotesque expressions. An art that makes the viewer wonder… Should I take a dagger to the thigh?

Women’s anger, when it makes its way into art, is often dressed up in tragedy—Mad Ophelia sinking into the river, Medusa a deterrent example, Judith slaying Holofernes but still looking poised and elegant. Although there are few examples of women in this state depicted in Pre-Raphaelite oil paint, those that do exist hold a special place in my mind’s gallery.

Take Artemisia Gentileschi, the original feminist painter, who pawed through the pages of the Bible story of Judith and Holofernes and said, “Let’s make this realistic.” The result? A painting where Judith isn’t just delicately smiting her enemy—she’s hacking at his throat with pure, unfiltered rage. Blood spurts. Tendons snap. Holofernes is not dying a cinematic death; he is dying ugly, and Artemisia made sure we knew it. This was personal.

Compare this to Caravaggio’s Judith Beheading Holofernes, where Judith’s expression is one of disgust and hesitance. She looks almost reluctant, as if she’s completing a distasteful chore. She wears an elegant white blouse, crisp and untouched by the carnage, making her seem distant from the violence she is committing. Meanwhile, Gentileschi’s Judith is fierce and determined, her sleeves rolled up, fully engaged in the act of revenge. She is not repulsed—she is resolute. This is the difference between painting a woman’s rage from the outside and painting it from within.

The theme of female suffering and defiance is also captured in Portia Wounding Her Thigh, where Portia, the wife of Brutus, self-inflicts a wound to prove her strength and ability to bear pain. A dramatic and guttural moment, this act is both an assertion of willpower and an act of desperation.

We also see this theme in Artemisia Gentileschi’s Lucretia, where Lucretia, moments before her tragic suicide, is painted with raw emotion. Unlike other depictions that focus on her beauty or the elegance of her suffering, Gentileschi gives her a sense of agency—her expression is one of painful resolve rather than passive despair.

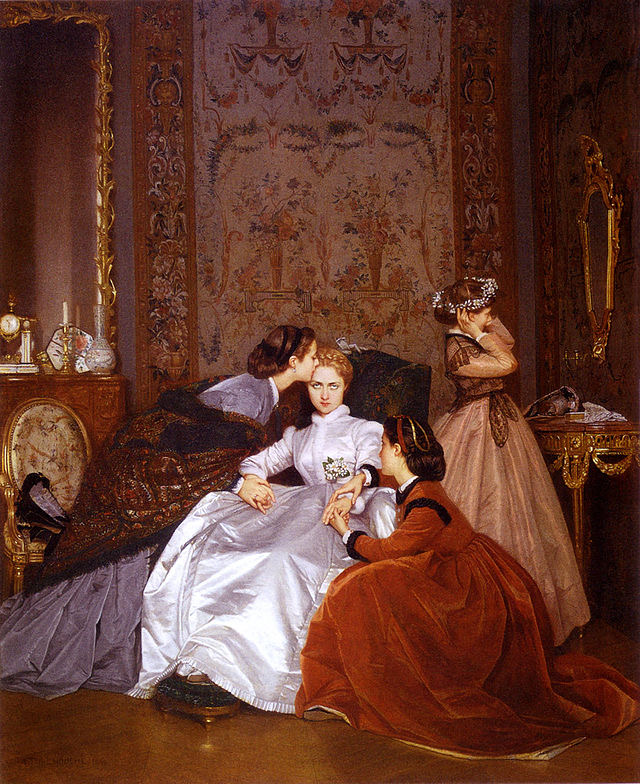

Even in more restrained works like Auguste Toulmouche’s The Reluctant Bride, the simmering frustration is present. The bride, adorned in silks, sits frozen in place, her body language betraying a deep reluctance. It’s a quiet, suppressed rage—the kind that has long been expected of women. The kind that doesn’t get to scream, but still refuses to disappear. It is all in the eyes.

The thing about female rage is that it has always been there, but the world has spent centuries trying to dull its edges. Art is where those edges get sharpened again. And frankly, there is nothing more powerful—or more satisfying—than that.

Chorus Leader: You would become the wretchedest of women.

Medea: Then let it be.

Leave a comment